The Problem

A large portion of energy produced worldwide is lost as waste heat from industrial processes, vehicles, and electronics.

A large portion of energy produced worldwide is lost as waste heat from industrial processes, vehicles, and electronics.

A research team developed a medium-entropy thermoelectric material that combines low heat flow with efficient electrical transport by leveraging hidden nanoscale structural features.

This approach could improve efficiency in industrial, automotive, and solid-state cooling applications by enabling devices to recover energy lost as heat.

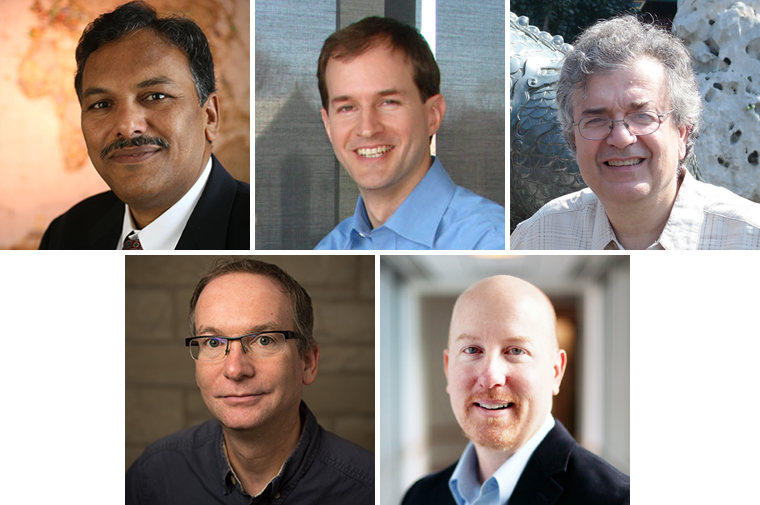

Former PhD student Yukun Liu (PhD ’25), Professor Vinayak Dravid, Professor Mercouri Kanatzidis, Professor Chris Wolverton, Professor G. Jeffrey Snyder, Professor Matthew Grayson, Research assistant professor Roberto dos Reis, et al.

A large portion of the energy produced worldwide dissipates as waste heat from industrial furnaces, vehicle exhaust systems, power plants, and even everyday electronics before reaching its intended use.

Thermoelectric materials offer a way to capture some of that lost energy by converting heat directly into electricity without moving parts, combustion, or emissions. Despite decades of research, however, practical deployment has been limited by materials that struggle to combine efficiency, durability, and performance across wide temperature ranges.

A new study led by scientists from multiple Northwestern Engineering research groups shows progress toward overcoming those limitations.

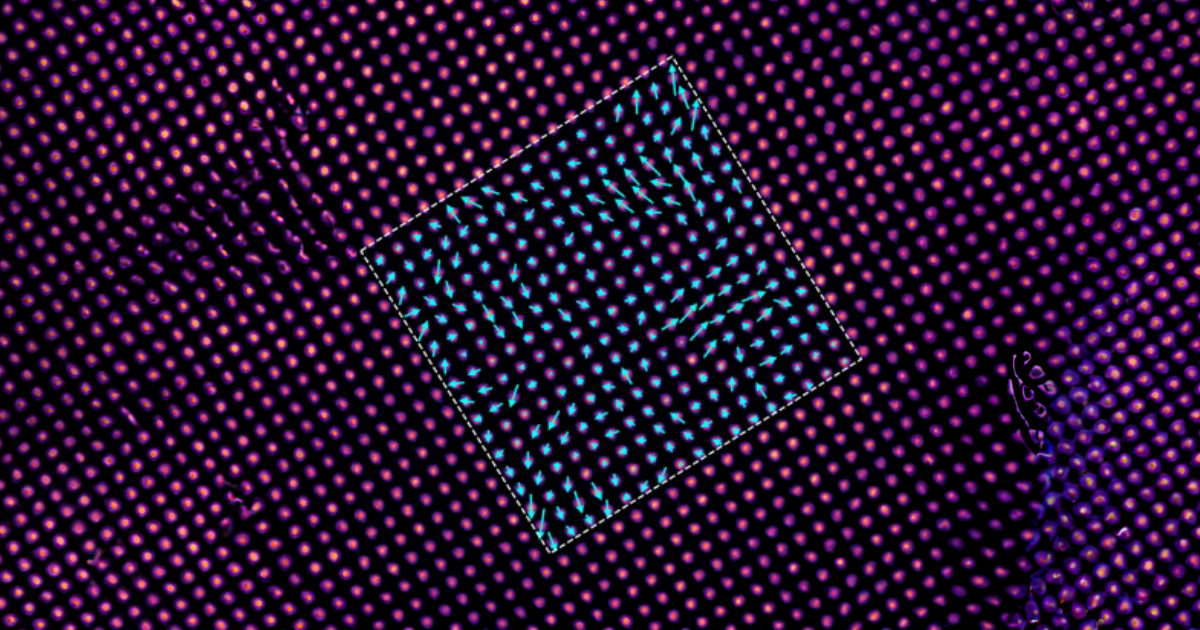

The team developed and characterized AgMnSbPbTe₄, a thermoelectric semiconductor that performs well from near room temperature to over 980 degrees, with hidden structural features revealed by advanced imaging that help turn waste heat into electricity. Conventional X-ray diffraction indicated the material was structurally homogeneous, a finding that advanced electron microscopy subsequently overturned. The imaging revealed nanoscale heterogeneity invisible to standard characterization, underscoring that entropy-engineered materials can harbor significant internal structure even when bulk techniques suggest uniformity.

“By combining high efficiency with performance over a wide temperature range, this material moves thermoelectrics closer to practical applications in industrial waste-heat recovery, automotive systems, and solid-state cooling,” said lead author Yukun Liu, who earned a PhD in materials science and engineering from the McCormick School of Engineering last fall.

The research was reported in the paper “Structural Heterogeneity in Medium-Entropy AgMnSbPbTe4 for Glassy Thermal Transport and High Thermoelectric Performance,” published Jan. 6 in the Journal of the American Chemical Society. Professor Vinayak Dravid served as the intellectual driver of the project and Liu’s academic adviser. Liu coordinated synthesis, transport measurements, and microscopy to connect atomic-scale features to macroscopic performance. Other contributors include Professor Mercouri Kanatzidis and his group, the research lab of Professor Chris Wolverton, Professor G. Jeffrey Snyder and his team, and Professor Matthew Grayson and his group.

Dravid is the Abraham Harris Professor of Materials Science and Engineering, Kanatzidis is the Charles E. and Emma H. Morrison Professor of Chemistry and (by courtesy) Professor of Materials Science and Engineering, Wolverton is the Frank C. Engelhart Professor of Materials Science and Engineering, Snyder is a professor of materials science and engineering, and Grayson is a professor of electrical and computer engineering.

The appeal of thermoelectric technology lies in its simplicity. Unlike turbines or engines, thermoelectric devices generate electricity through solid-state physics. When one side of a material is hot and the other is cool, charge carriers move, producing an electric current. This makes thermoelectrics well suited for harsh or remote environments, as well as for applications where reliability and low maintenance are critical. Examples include industrial waste-heat recovery, automotive systems, and solid-state cooling.

For thermoelectrics to be useful at scale, materials must efficiently conduct electricity while blocking the flow of heat. These requirements are often in tension. Structures that scatter heat-carrying vibrations also tend to impede electronic transport.

“Our new material addresses this challenge by exhibiting glass-like thermal conductivity while retaining crystal-like electrical properties,” Dravid said. “This enables efficient operation across a broad temperature window relevant to many waste-heat sources.”

Understanding how the material achieves this balance required an unusually interdisciplinary effort.

Higher-resolution electron microscopy revealed that, unlike what standard X-ray tests suggested, the material contains tiny regions with slightly different compositions and small distortions in its atomic structure. These features block heat flow while allowing electricity to pass efficiently, explaining the material’s strong performance across a wide temperature range and showing that multi-element materials can have important internal structure even when they appear uniform.

Electron ptychography allowed the researchers to form images of individual atoms by analyzing how electrons scatter as they pass through the material. Because the method is technically demanding, it has most often been applied to simpler, well-defined model systems. Extending ptychography to a chemically complex, multicomponent thermoelectric, where compositional heterogeneity complicate analysis, represents a methodological step forward for the technique.

In this case, the team applied it to a chemically complex thermoelectric material used for energy conversion. The images revealed small shifts in atomic positions linked to the material’s mixed composition, providing direct insight into how its internal structure affects overall performance.

Materials synthesis was led by the Kanatzidis group, with additional support from Argonne National Laboratory. Advanced microscopy was carried out by the Dravid group at Northwestern's NUANCE Center. Electron ptychography was deployed and adapted by scientific officer and research assistant professor Roberto dos Reis to address the specific challenges of this multicomponent system. Computational modeling and bonding analysis were performed by the Wolverton group, while thermoelectric transport measurements involved the Snyder and Grayson groups, with low-temperature studies conducted at the Max Planck Institute in Dresden, Germany.

“This integration of synthesis, microscopy, theory, and transport measurements was essential. No single approach could have connected atomic-scale structure to device-relevant properties on its own,” dos Reis said. “The collaboration allowed us to move from hidden structural features to measurable performance, illustrating how modern materials research increasingly relies on coordinated expertise.”

“This integration of synthesis, microscopy, theory, and transport measurements was essential. No single approach could have connected atomic-scale structure to device-relevant properties on its own,” dos Reis said. “The collaboration allowed us to move from hidden structural features to measurable performance, illustrating how modern materials research increasingly relies on coordinated expertise.”

Building on Liu’s earlier research into how mixing multiple elements influences structure and heat flow in thermoelectric materials, this study shows that medium-entropy compositions can produce useful nanoscale features while still maintaining efficient electrical transport.

Looking ahead, the researchers plan to test AgMnSbPbTe₄ in device-level configurations and to explore similar strategies in related materials systems. They also aim to develop complementary materials needed for full thermoelectric modules and to assess long-term stability under operating conditions.

“The work illustrates how advanced characterization techniques can unlock practical advances in energy materials,” Dravid said. “By revealing structure that governs performance but remains hidden to conventional tools, interdisciplinary approaches like this one can help translate fundamental discoveries into technologies capable of recovering energy that is currently lost to heat.”