Deepfake-Detection System Is Now Live

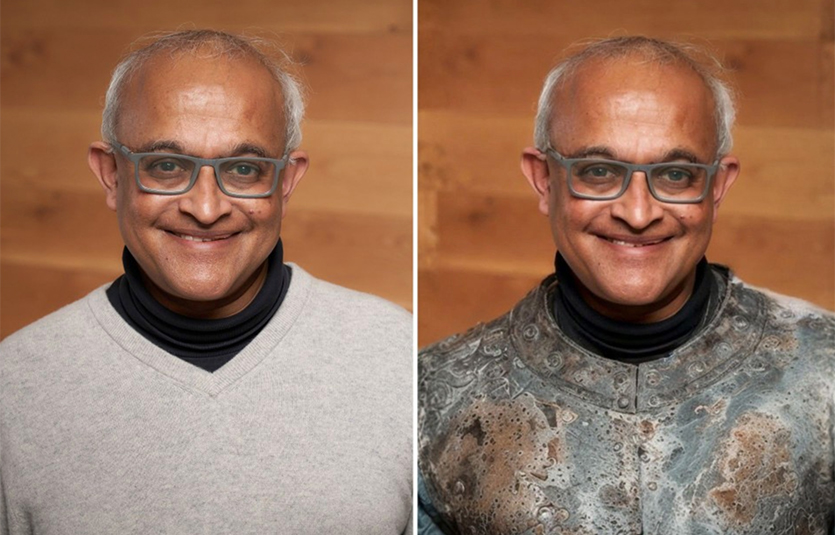

Subrahmanian developed a free platform to help journalists determine the validity of digital artifacts.

Not all deepfakes are bad.

Deepfakes — digital artifacts including photos, videos and audio that have been generated or modified using artificial intelligence (AI) software — often look and sound real. Deepfake content has been used to dupe viewers, spread fake news, sow disinformation, and perpetuate hoaxes across the internet.

Less well understood is that the technology behind deepfakes can also be used for good. It can be used to reproduce the voice of a lost loved one, for example, or to plant fake maps or communications to throw off potential terrorists. It can also entertain, for instance, by simulating what a person would look like with zany facial hair or wearing a funny hat.

“There are a lot of positive applications of deepfakes, even though those have not gotten as much press as the negative applications,” said V.S. Subrahmanian, Walter P. Murphy Professor of Computer Science at Northwestern Engineering and faculty fellow at Northwestern’s Buffett Institute for Global Affairs.

Still, it’s the negative or dangerous applications that need to be sniffed out.

Subrahmanian, who focuses on the intersection of AI and security issues, develops machine learning-based models to analyze data, learn behavioral models from the data, forecast actions and influence outcomes. In mid-2024 he launched the Global Online Deepfake Detection System (GODDS), a new platform for detecting deepfakes, which is now available to a limited number of verified journalists.

For those without access to GODDS, Subrahmanian offered five pieces of advice to help you avoid getting duped by deepfakes.

Anyone with internet access can create a fake. That means anyone with internet access can also become a target for deepfakes.

“Rather than try to detect whether something is a deepfake or not, basic questioning can help lead to the right conclusion,” said Subrahmanian, founding director of the Northwestern Security and AI Lab.

For better or for worse, deepfake technology and AI continue to evolve at a rapid pace. Ultimately, software programs will be able to detect deepfakes better than humans, Subrahmanian predicted.

For now, there are some shortcomings with deepfake technology that humans can detect. AI still struggles with the basics of the human body, sometimes adding an extra digit or contorting parts in unnatural or impossible ways. The physics of light can also cause AI generators to stumble.

“If you are not seeing a reflection that looks consistent with what we would expect or compatible with what we would expect, you should be wary,” he said.

It’s human nature to become so deeply rooted in our opinions and preconceived notions that we start to take them as truth. In fact, people often seek out sources that confirm their own notions, and fraudsters create deepfakes that reinforce and affirm previously held beliefs to achieve their own goals.

Subrahmanian warns that when people overrule the logical part of their brains because a perceived fact lines up with their beliefs, they are more likely to fall prey to deepfakes.

“We already see something called the filter bubble, where people only read the news from channels that portray what they already think and reinforce the biases they have,” he said. “Some people are more likely to consume social media information that confirms their biases. I suspect this filter-bubble phenomenon will be exacerbated unless people try to find more varied sources of information.”

Subrahmanian developed a free platform to help journalists determine the validity of digital artifacts.

Subrahmanian and Professor Daniel Linna Jr. are examining the emerging technology’s potential harms to democracy.

A report co-authored by Subrahmanian outlined recommendations for defending against deepfakes.

A study from Subrahmanian found that incursions into Aksai Chin region are not random, independent events.

Already, instances have emerged of audio deepfakes being used by fraudsters to try to trick people into not voting for certain political candidates by simulating the candidate’s voice saying something inflammatory on robocalls. However, this trick can get much more personal. Audio deepfakes can also be used to scam people out of money. If someone who sounds like a close friend or relative calls and says they need money quickly to get out of a jam, it might be a deepfake.

To avoid falling for this ruse, Subrahmanian suggests setting up authentication methods with loved ones. That doesn’t mean asking them security questions like the name of a first pet or first car. Instead, ask specific questions only that person would know, such as where they went to lunch recently or a park where they once played soccer. It could even be a code word only relatives know.

“You can make up any question where a real person is much more likely to know the answer and an individual seeking to commit fraud using generative AI is not,” Subrahmanian said.

Social media has changed the way people communicate with each other. They can share updates and keep in touch with just a few keystrokes, but their feeds can also be filled with phony videos and images.

Subrahmanian said that some social media platforms have made outstanding efforts to stamp out deepfakes. Unfortunately, suppressing deepfakes could potentially be an act of free speech suppression. Subrahmanian recommends checking websites such as PolitiFact to gain further insight into whether a digital artifact is a deepfake or not.